In work that could open a floodgate of future applications for a new class of nanomaterials known as MXenes (pronounced “Maxines”), researchers from Texas A&M University have discovered a simple, inexpensive way to prevent the materials’ rapid degradation.

Two-dimensional MXene nanosheets have promise in applications ranging from energy storage to water purification. However, MXenes have an Achilles’ heel: they rapidly degrade when kept in the open.

According to the Texas A&M team, the solution to this problem involves exposing MXenes to anything in a family of compounds best represented by a natural dietary supplement such as vitamin C.

“With these findings, shelf-stable MXenes become possible and engineering-grade MXene-based materials can become a practical reality,” the researchers wrote in a paper for the upcoming issue of the online journal Matter.

Interesting Properties

Discovered in 2011 by a team at Drexel University, MXenes are sheets of materials only a few atoms thick that are mostly composed of layers of metals like titanium interleaved by carbon and/or nitrogen.

Due to their nanothickness and the variety of elements they can be composed of (other nanomaterials like graphene contain only carbon), “these materials tend to have really interesting properties, like high electrical conductivity and high catalytic activity,” said Dr. Micah Green, an associate professor who led the work and has joint appointments in the Artie McFerrin Department of Chemical Engineering and the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at Texas A&M.

As a result of those properties, MXenes have generated a great deal of interest and enthusiasm in the research community with potential applications in everything from batteries to electronic sensors.

“But there has been one problem lurking in the background,” said Green. MXenes degrade, or oxidize, quickly. “They fall apart and stop being nanosheets. This happens in a matter of days.”

Although other researchers have found that techniques like drying or freezing MXenes can delay their degradation, “they’re still not going to last for years,” he said. “And no one wants a material that doesn’t have a long shelf life.”

Texas A&M tackled the problem through an interdisciplinary team of experts in nanomaterials, ceramics and polymers.

The other faculty members involved in the work are Dr. Miladin Radovic, professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, and Dr. Jodie Lutkenhaus, associate professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering and the Department of Chemical Engineering.

Toward a Solution

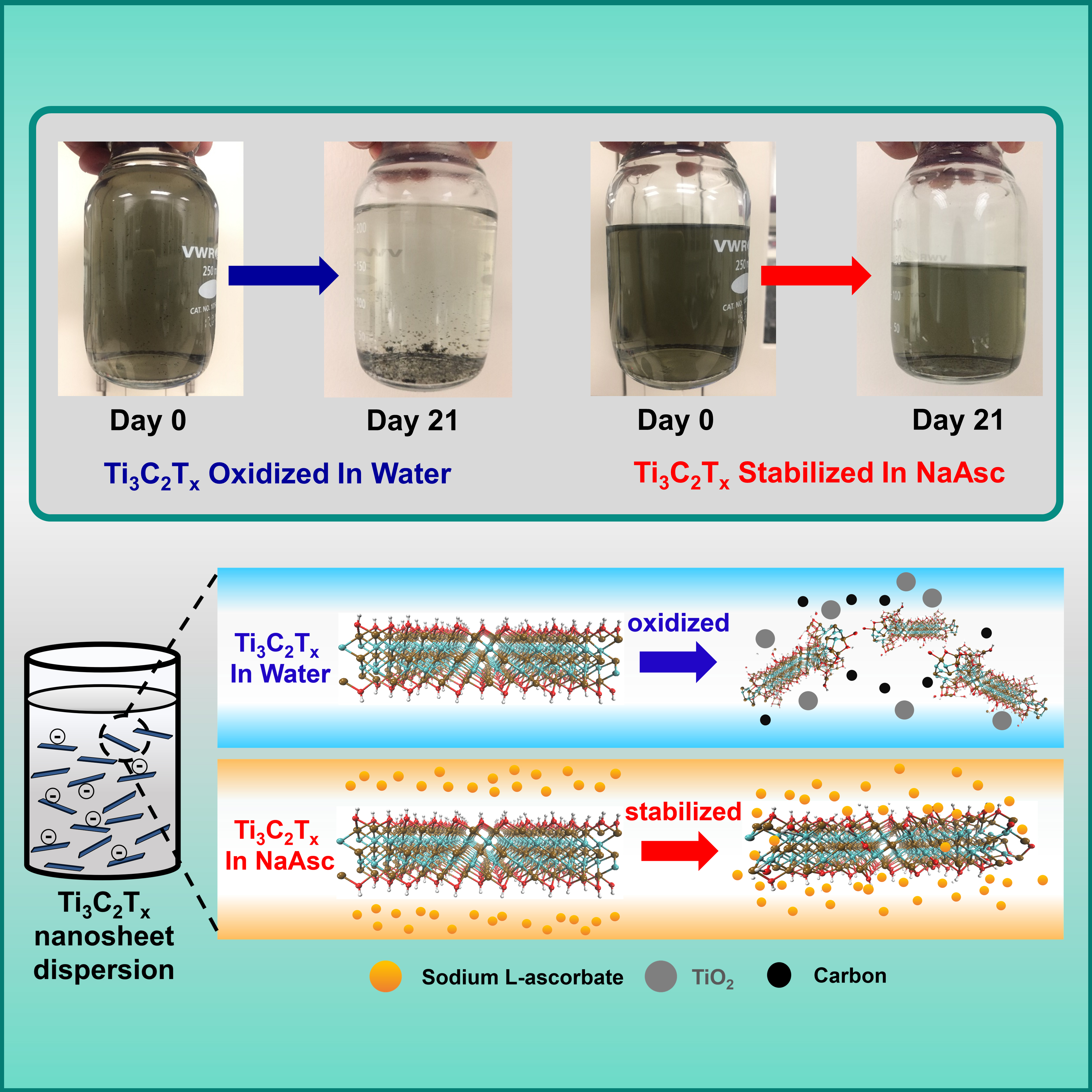

The team ultimately found that exposing a typical MXene to a solution of sodium L-ascorbate stopped the nanosheet from degrading. Plus, several related compounds, including vitamin C, also worked. According to Green, the effect lasts. He also noted that the team made the discovery about a year ago and the treated MXenes are still stable.

To further investigate the phenomenon leading to the improved stability, the team completed molecular dynamics simulations of the interactions between the MXenes and the antioxidants. They found that the ascorbate molecules appear to associate with the MXene nanosheet, preventing it from interacting with water molecules and as a result, shielding it from oxidation.

The team is excited because their “method appears to work with a variety of different MXenes,” Green said. The Matter paper focuses on the most common MXene (Ti3C2Tx), but other types of MXenes are even more unstable. So much so that “people have doubted whether those materials could ever find applications. With this technique, that could change. The researchers are currently exploring the stability of these additional MXenes using the same approach.

“Our hope is that everybody who works on MXenes, including people in industry, will use our technique to protect their materials,” said Green.

The co-authors on the Matter paper are Xiaofei Zhao, Aniruddh Vashisth, Wanmei Sun, Smit A. Shah and Touseef Habib from the Department of Chemical Engineering; and Evan Prehn, Yexiao Chen and Zeyi Tan from the Department of Materials Science and Engineering.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation.