Perhaps the most common turn of phrase for complexity is “It’s not rocket science.” It’s usually said to offset a task that is becoming more difficult than it otherwise should be. In the case of one ocean engineering senior design capstone team, however, it’s the opposite.

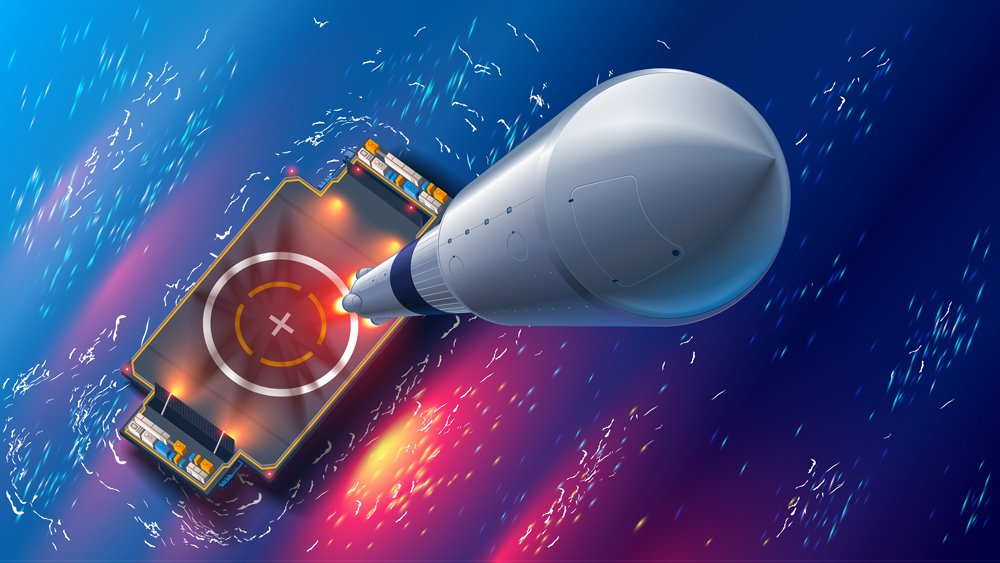

Working as a trio, Konnor Chappell, Robert Jackson and Daniel Jansen are designing an offshore rocket platform for launches and landings.

“Basically, we're taking a large vessel – a big drilling ship, semisubmersible, one of these big vessels – and converting it into a rocket pad,” said Chappell. “It sounds kind of simple when you put it that way, but it's not really been done a lot historically. We have seen it a little bit in the late 90s to kind of base our design off of, but really, this is an emerging technology to even think about using an offshore launch platform.”

The previous example of using a floating platform as a rocket launch pad came from the petroleum industry, in which an old drilling platform was converted into a launch pad for smaller rockets and satellites. Unfortunately, most of the technical information about the launch pad used at that location is proprietary and not available to the public. Economic and financial issues closed the operation and led to no further advancement in the technology.

As Jackson described, the openness of the ocean offers both safety and convenience for professionals and spectators, making it a viable and obtainable location option for future launches. With every rocket launch, there are exclusion zones – areas that must be kept clear of people. As rockets get bigger, as they will need to be with Mars missions and other space exploration plans, the exclusion zones will also get larger to accommodate them.

“So, you’re either going to have to move people or you’re going to have to move the rockets to being launched from the middle of a mountain range and develop an entire infrastructure for it,” said Jackson.

He explained that while converting an already existing vessel negates the need for new infrastructure, there are still several challenges that the team faces in the design of their project. For example, the motion dynamics of a launch. In addition to a massive rocket sitting on a floating structure, they have to take into account the millions of pounds of thrust that will push down on the launch pad and find a way to counteract it.

Calling upon their ocean engineering background, the team has already started brainstorming ways to counteract such issues. Chappell, who will be leading the computational modeling and simulation front, explained that the team plans to utilize technology from several ocean and marine industries – combining the best characteristics of each to help offset the stress the platform will be under.

“It’s a complex project, but if we can design it, we can help bring ocean engineering into the spotlight and show how important this small field is to the petroleum, aviation and aerospace industries,” said Jackson.

Inspired by NASA’s space exploration missions, as well as the visions of SpaceX and their reusable rockets, the team is eager to continue their work and develop their idea further throughout the spring.

“I think actually proving that this thing will do it and doing a response simulation and being able to show you, plain as day, the platform is holding up as the rocket takes off is exciting,” said Jackson. “You’d be able to see some of the different responses. It might go beyond the scope of what the capstone project is to do a simulation animation model and rule, but to be able to actually prove that our work would fit into this and benefit the platform and hold up under the stresses would be my goal.”

“I want to add to that there is some software that I've been looking into that we can use to model the force from the rocket onto the vessel itself,” said Chappell. “I think something really exciting will be to show anybody this simulation and how it works and have them be like, ‘Holy cow, that's a rocket taking off on a boat.’”