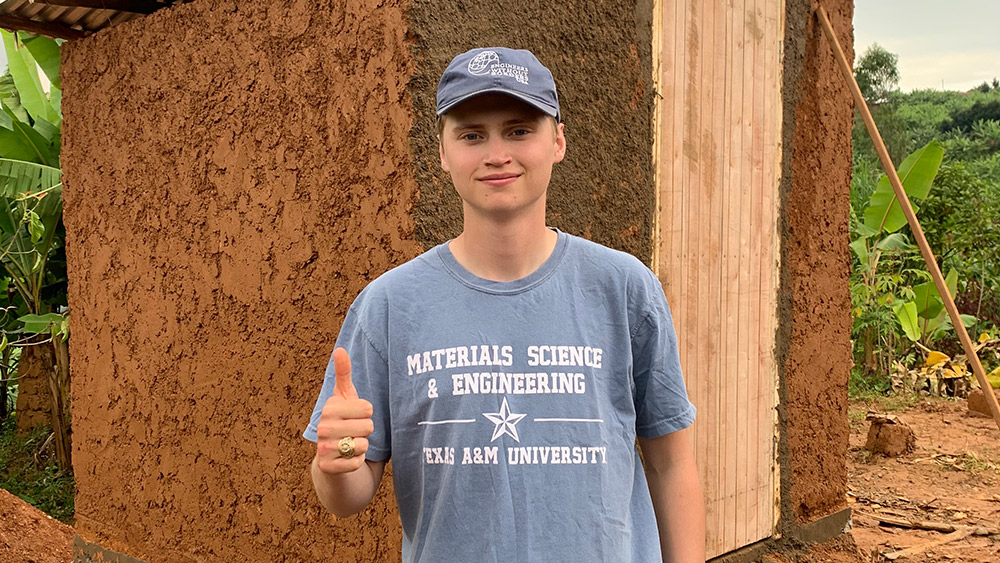

After a twice-delayed trip to Rwanda to build latrines, Eli Norris, a senior in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, had an eye-opening experience that reinforced his career goals.

Norris, along with five other students and a professional mentor, traveled to Rwanda in May for Engineers Without Borders (EWB-TAMU) and spent 11 days embedded in the culture of Matyazo.

“Working on these projects was eye-opening and culturally significant,” Norris said. “It’s been a unique experience to see into the lives of people completely across the world. It helped reinforce that whatever I end up doing, I want it to matter. I want it to make a difference.”

In January 2020, Norris joined EWB-TAMU to contribute to something meaningful and continued to move up the ladder in the organization and eventually became the vice president of projects.

“I joined because we got to do something that matters while we’re here in college,” Norris said. “I wanted to move up into more of a leadership role instead of just being the guy who does my few tasks. After doing that for a semester, I became a sub-team leader and led a small group of students. I enjoyed doing that, and it led me to be a project lead.”

As vice president of projects, Norris took over the latrine project right after an assessment trip conducted in 2020. He drew out the latrine and created a 3D model that he completed in 2021.

The project was a collaborative effort between EWB-TAMU and the Rwandan community for four years to improve sanitary and agricultural conditions.

“It was an educational experience because I was managing this project, which was international, so we’re talking to people in Rwanda that don’t speak English,” Norris said. “Figuring out how to communicate with someone whose first language is not English was something we had to do. I learned how to manage people, delegate tasks and keep everyone motivated. I discovered a lot about project management and the softer skills to be a successful engineer.”

The original plan was to go over the summer of 2021. However, the trip had to be postponed because of COVID-19. The trip was delayed for a second time after the omicron variant ramped-up

With the outline of the latrine already in place, Norris and his team did a remote implication with the community of Matyazo. They built the first latrine with instructions from EWB-TAMU in College Station, Texas.

“We created detailed instruction manuals,” he said. “It was almost like a Lego set on how to build the latrine. We sent that and the funding to them. They built the first one with our remote support in April. After that, we finally made the trip happen in May. They already knew how to build the latrines, so when we were there, we worked with them, giving pointers and tips.”

When Norris arrived with the team, they built the latrine on the hillside due to the lack of flat land and built a square box with stones carried from the river up the mountain.

Local stonemasons were employed to break the stones into rectangles, and a mixture of cement, sand and water was used in between the stones. A concrete slab formed the pit where the waste goes, and the superstructure was made of mud bricks.

“The cool thing about these latrines is that everything they’re made out of is crafted locally, so we’re not having to import from the U.S.,” he said. “We can help them with the sanitation problem and stimulate their economy by purchasing materials from local people and using local labor to build them.”

The first latrine was built by the community before the EWB-TAMU team’s arrival, and the second was built while they were there. The third, fourth and fifth are now completed, and the sixth, seventh and eighth are about to be constructed.

“We want to build more than 100, and we can’t be there for most of them, so we tried to figure out a way that allows them to build with our remote support,” Norris said. “This idea is cool because it’s new to engineering and construction. Normally you want to be onsite watching it.”

With the hurdles the team and Norris have overcome, Dr. René Elms, associate professor of practice and primary advisor for EWB-TAMU, has been extremely impressed with the project's progress.

“Even with the challenges and postponements due to COVID, they were very resourceful in developing an effective strategy to keep moving forward,” Elms said. “Their tenacity and sincere desire to serve the community members provide a powerful example of what it truly means to be an Aggie engineer.”

Funding for the project came from EWB-TAMU — which raised 95% from fundraising — and local engineering companies and private businesses. Each latrine takes about $500 to build and will last up to 20 years.

“We learned a lot; there were many things they taught us that we would have never thought of,” Norris said. “One was the process of pouring the concrete slab. We originally planned to pour the slabs and lift them on top of the pit, but they decided to create supports in the pit and pour the concrete directly on top.”

Although that was not in the previous design, Norris said it was more efficient because builders don’t have to lift the slabs and worry about anyone getting hurt.

“When we were building the latrine, people from the community started bringing supplies,” Norris said. “Seeing the sense of community they have and how much they care about each other and how hardworking they are made me realize we take advantage of a lot of things, and we should be happy even when stuff doesn’t go our way.”