Scalpels, scissors, drain tips, needles, clamps — these are just a few handheld instruments used before, during and after surgery. But how do medical professionals ensure all these tools are accounted for after the surgery? The method of accounting for the tools is by a handwritten checklist, which can result in human error.

A team of biomedical engineering students from Texas A&M University worked on a solution to reduce the chance of these instruments being left inside patients by creating a reliable instrument table.

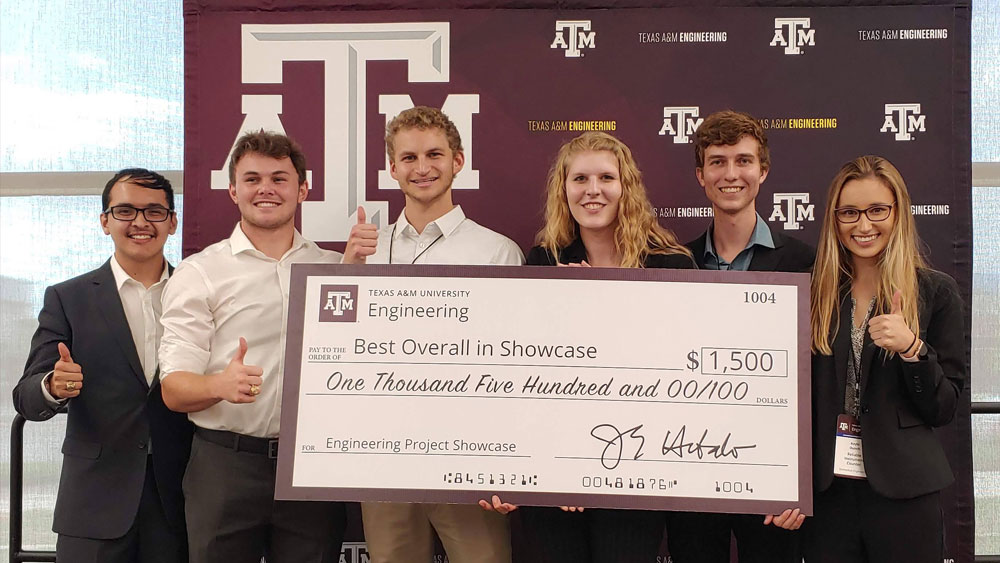

“The Reliable Instrument Counter (RIC) team won the overall engineering project showcase with their counter, which is a big deal," said Dr. Charles Peak, biomedical engineering instructional assistant professor.

The College of Engineering’s 2022 project showcase included more than 1,100 students and 245 teams. The selection of RIC as the strongest overall team members’ technical skills, design knowledge and ability to convey the need and value of their device.

Currently, scrub technicians at hospitals in the United States use manual counting to track the instruments and tools utilized during surgery, which increases the hospital’s cost, tool miscounts and patient safety.

"We've heard of a story once or twice where someone is not feeling right after surgery and then realizes, ‘Oh, something is in me,’” Peak said. “That happens more than hospitals care to admit. That's not an ideal outcome.”

The team decided to use radio-frequency identification readers to tag the different instruments. The RFID chips are connected to a table that lights up green when the tool is returned.

According to Michael Fink, team member and former biomedical engineering student, this "smart" table solution integrates RFID technology while ensuring that the surgical instrument count is accurate and quick.

"We approached this by trying to find the best method of hands-free counting objects in general," Fink said. "Our research and real-life experiences ultimately led us to the use of RFID for detection of instruments, and that's where the fun, and sometimes the pain, began."

The RIC team used already developed software and added the RFID technology, which only requires one extra computer screen in the operation room.

"They added their device to the underside of a table, and then with tagging all their instruments, they were able to instantaneously get a digital read whether the instrument was present or not present," Peak explained. "Any instrument used would show as not being on the table."

This table solution has the potential to significantly decrease the time spent in the operating room and simultaneously ensure patient safety.

"The operating room cost is $62 per minute and the average amount of time to count instruments is 8.6 minutes, meaning manual counting costs the hospital $533 for every procedure, assuming there are no discrepancies," team member Cayman Myers said.

Drs. Chester Koh, Hannah Bachtel and Soo Kim from Texas Children's Hospital sponsored the project.

"They provided valuable insight into their field," said Shelby McCoy, a third team member. "This relationship has been beneficial in many ways, particularly seeing how we can continue giving back to the community as rising professionals. It was encouraging to see how these physicians incorporated academics and research into their careers."

The RIC capstone team also included Daniel Aguilar, Kayla Dunch and Jack Gibbs. Each of the team members has taken their own path since the project’s completion in May 2022.

Aguilar and Dunch have both entered industry: Aguilar is a technical systems engineer at Epic Systems and Dunch is now a consultant at Philips Healthcare. Fink and Gibbs are pursuing graduate degrees: Fink is completing his master’s degree in biomedical engineering and Gibbs is pursuing a master’s in biotech commercialization at The University of Texas at San Antonio. McCoy and Myers are taking a gap year while they apply to medical school: McCoy is a cardiovascular research intern at Baylor Scott & White Research Institute, while Myers is currently a research and development engineer at Nanomedical Systems.

"As a team overall, they did a lot of extra work and a lot of self-motivated and independent learning," Peak said. "As an instructor, I am proud of them for that. I expect they will continue to apply engineering fundamentals in their future roles."