People typically experience urinary tract infection (UTI) symptoms, such as pain while urinating or pelvic cramps, before knowing germs have invaded the bladder. Despite the average success of antibiotics, a UTI can pose a significant risk to medically vulnerable populations if diagnosed too late or left untreated.

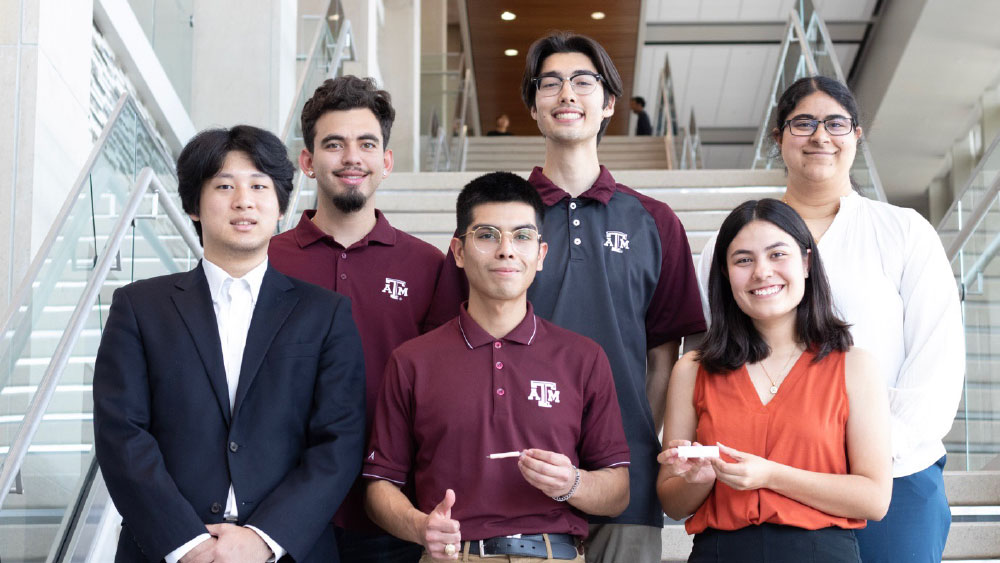

A capstone team of six seniors in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Texas A&M University, known as Infection Detection, was prompted by medical technology company Becton Dickinson (BD) to develop a method to quickly detect an oncoming UTI in one of those vulnerable populations — ureteroscopy surgery patients.

A ureteroscopy procedure involves inserting a small scope through the bladder into the ureter, the duct where urine travels from the kidney to the bladder. Normally, a ureteroscopy is used to find and remove ureteral stones and, in some cases, remove kidney stones. While infections are not commonplace with ureteroscopies, they can be risky if they appear.

“The typical timeline for detecting a post-operative infection is about three to four days after the surgery, usually when the patient presents with symptoms,” team member Vibha Sheshadri said. “Their symptoms can range anywhere from typical UTI symptoms to full-blown urosepsis, which can be fatal. The idea is to catch it as soon as possible so doctors can administer post-operative antibiotics.”

To give physicians the ability to rapidly test for the bacteria typically linked to UTIs, the team set out to find a way to collect a sample during the ureteroscopy procedure. The goal was to avoid additional steps or invasive measures, so instead of reinventing the wheel, they aimed to improve the current procedure process.

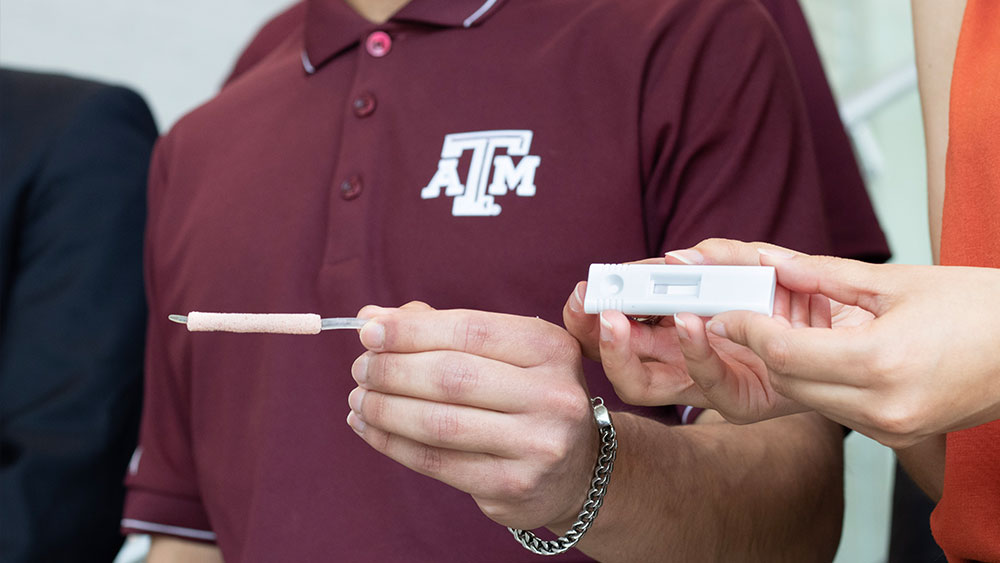

“During a ureteroscopy, there's a guidewire that leads into the ureteroscope,” team member Izaiah Ramirez said. “We are approaching this problem by replacing the tip of the existing guide wire system with a collection device. This tip would essentially screw on and collect a viable urine sample we would take once removed from the urinary tract.”

Once the sample was collected, the team’s next challenge was to define and measure markers consistent with an infection. For this part of the problem, Infection Detection found mentorship from graduate students in the Nanotheranostics Lab, run by Dr. Samuel Mabbott, assistant professor in the biomedical engineering department.

Due to the graduate students’ experience with lateral flow assays, a similar technology to an at-home rapid COVID or pregnancy test, Infection Detection had resources to create a quick testing process.

“They were really helpful in providing those resources and helping with protocols and just giving us a lab space to work with the lateral flow,” Ramirez said. “It was really nice learning from current grad students who are in this field and can help us see our way through.”

Along with assistance from the Nanotheranostics Lab, Infection Detection also checked in weekly with Peter Winsauer, a former student of the department and current associate research and development engineer at BD, to get feedback and guidance on their device design and tackle any prototyping challenges.

The team’s method includes an overnight incubation process and a two-hour result development, a direct improvement from the current days-long diagnosis process. However, Infection Detection believes with more optimization tests, the time can be shortened even more.

“Whether these ideas go further or not, it's amazing to see what we could come up with and even develop so quickly with so little budget,” Sheshadri said. “It gives me a lot of hope that in the next five to 10 years, we're going to see some amazing advancements in biomedical engineering and health technologies.”